For October, we decided to include TWO QUESTIONS from two photographers, Magdalena Sole and John Masters (find out more about them below). In this same vein, please feel free to leave TWO COMMENTS –– one about one of Rebecca’s responses, one about one of Alex’s –– after this posting. ––AW and RNW

MAGDALENA SOLE: Rebecca, you talk about returning to a place like Cuba some eleven times. How do you keep that initial fresh eye –– that untainted first impression that helps one see the image? What changes when you return again and again to the same place?

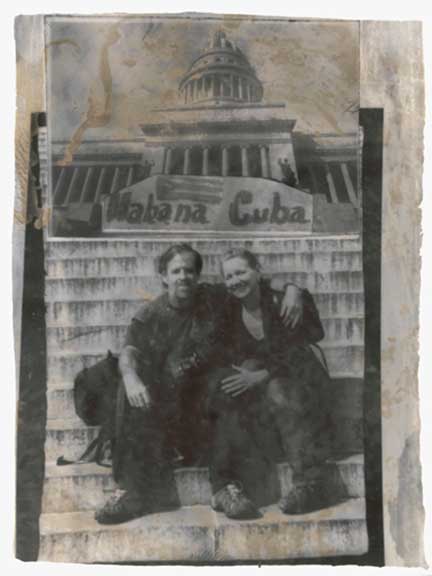

RNW, Remedios, Cuba, 2008

RNW: Good question, Magdalena. You know, I’ve never really thought about it, but I think, for me at least, I tend to discover fresher and more unique images in a place the more trips I make. It’s somewhat akin to love. You can fall in love at first sight, but it takes considerably longer to understand the nuances, the strengths and weaknesses, and the uniqueness of that person you’re in love with.

So for me, I don’t tend to have the experience you mention my first trip to a place – the fresh and untainted impression you mention. I find it’s only after at least two or three or perhaps more trips to a place that my vision tends to deepen and I begin to see the place in a more unique and complicated way, perhaps echoing my experience of getting better acquainted with a place.

MAGDALENA SOLE: Alex, you once told me that you walk for miles every day to find your pictures, but then you also remain put in one place for hours. When you stay in one place, do you start talking to the people and connecting with them, or do you remain on the periphery? Later, do you go back to people and places you know?

AW: Every situation is different. In some situations it works for me to just walk through the situation, photographing and rarely talking to anyone. But in other situations, especially when I end up hanging out for extensive periods of time, I certainly will talk — as well as of course watch and wait. If I sense the possibility of a picture, but it doesn’t happen that day, I may return another day — or even, occasionally, another week, another month, or another year. I try to work with whatever the world gives me.

JOHN MASTERS: Alex, does the philosophy of magical realism allow you to see something through the viewfinder or in an image that perhaps others do not see or feel?

AW, Parintins, Brazil, 1993

AW: When photographing in the Brazilian and Peruvian Amazon I sometimes felt as if I was stepping into the background of a magic realist novel. In the Amazon, the fantastic often seems to encroach on the mundane: at festivals people build immense floats depicting Amazonian creatures, children dress as huge fish for Earth Day, and monkeys and coatimundis are kept as household pets. Would I have responded differently to such phenomenon if I had not read Garcia Marquez and Vargas Llosa? I would guess the answer is both yes and no. My fascination with such phenomenon may well be more attuned, more intense, because of my readings. On the other hand, irrespective of any knowledge of magic realism, it’s pretty hard not to be taken in by the spectacle of fifteen-foot-high paper mache and plastic anacondas, tarantulas, and mermaids at the Boi-Bumba Festival in Parintins.

JOHN MASTERS: Rebecca, do you try to convey any specific emotion that you may have towards one of your images to the observer or would you rather they interpret the image in their own way?

RNW: Like poetry, what I love about photography is its suggestiveness, how an image –– whether in poetry or photography –– will resonate in different ways for different people.

That said, I am especially intrigued with people’s complicated response to the natural world –– emotionally, politically, philosophically. The challenge is how to visually convey the philosophical paradoxes and emotional tensions that define our experience of this complicated eco-political terrain. Each project I’ve worked on is a variation on this theme. For instance, in my current work-in-progress, My Dakota, my most personal project to date, I only recently realized that this project is about “looking for a contradiction to inhabit,” as the poet, Rilke, once wrote. For me, that contradiction is trying to photograph South Dakota’s “geography of hope” (as Wallace Stegner once famously called the West) and “geography of loss,” my brother’s death and his eternity. For me, the contradiction I’m trying to inhabit is My Dakota.

Magdalena Sole, Venice, 2008

Magdalena Solé was born in Reus. When she was seven her family departed Franco’s Spain in the middle of the night. The why is an unrevealed family secret. Life in 1960’s Switzerland for émigré Spanish was like life in 1950s New York City for Puerto Ricans—fitting in was a full time job. By 20 she was long fluent in Swiss German, could pass as a native and graduated as one of only two Spaniards from a University with a degree in teaching. As a teacher the pay was good and the future was bright, but the world beckoned. In the mid –1980s Magdalena arrived in New York City, illiterate in English and living in a walk-up on the lower East Side. She became married, had a son and found herself poor. Then life veered.

In 1989, when global branding was a little-known field, Magdalena founded and ran a graphic design business, TransImage, that specialized in translating visual and verbal images for different counties. By this time she spoke seven languages fluently and had lived in four different countries, so she understood how confusing cultural idiosyncrasies could be. The business, located in Tribeca with offices in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, thrived for twelve years until she sold it and attended Columbia Film school. She graduated with a Masters of Fine Art in 2002. Magdalena loved making film and wrote, directed and produced her own, A Zen Tale, which had a New York theatrical run. It was such a thrill to see her film’s name on a Manhattan marquee. Her last film, Man On Wire, on which she was the Unit Production Manager, won an Oscar in 2009. Despite her accomplishments, film was just too much business, with too many people, too big a budget and too little art. But she loved that camera and the images she could create. She still wanted to explore the world of image and story.

Photography was the perfect medium. No gaffers, gofers, best boys, script girls or craft services. Just her, the light and a subject. The Leica rangefinder became her partner in this exploration. For the past two years Magdalena has worked exclusively in photography. Her current project, Forgotten Places, is her road to the interior of the cities she loves. These urban environments exist at the edges, in immigrant and working class communities where beauty is found in displaced spirits and peeling paint.

Magdalena’s website: www.solepictures.com

John Masters, Roma family

John Masters was born in Europe to American parents in the mid-1960s. For the first year of his life, he smelled the heat of Italy and southern France–limestone, lavender and rosemary bushes mixed with salt and diesel. He answered to ‘Giovanni’ for several years. His first camera was a Kodak Instamatic in 1972. Then there were a series of Polaroid devices, until 1990, when he purchased his first film SLR, the sturdy workhorse Canon AE-1. He used this one camera for almost ten years. It once fell a short distance off a balcony in Florence, bouncing off the marble stairs below, yet survived. Four years later, after suffering from progressive shutter-ping, its internal workings ceased. This was Bulgaria 1999, and Masters’ life had changed dramatically.

Through a series of fortuitous events, he found a pattern in the world-fabric worth following. He fell in love again with travel, and those magical places we find ourselves when we go. In mirrors and windows he discovered secret doorways leading to abstract realms; in bus stations he waited while time shifted around him. He found himself speaking foreign tongues, listening to wild sounds, and relishing the zest of unexplored philosophical cuisine, especially Macedonian charcuterie. He developed a love of intellectual investigation which also fuels his eye. Like Jean Cocteau, he believes that “The camera is but the third eye of the person using it.” With his camera and notebook in hand, he is a visual cartographer; stopping to smell the roses, chat with a shop-keeper, have tea with a friend, and watch the river flow.

John Masters lives in upstate New York on an old farm. He uses several different cameras. He still uses a Canon AE-1.